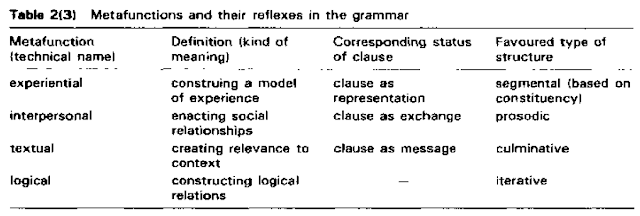

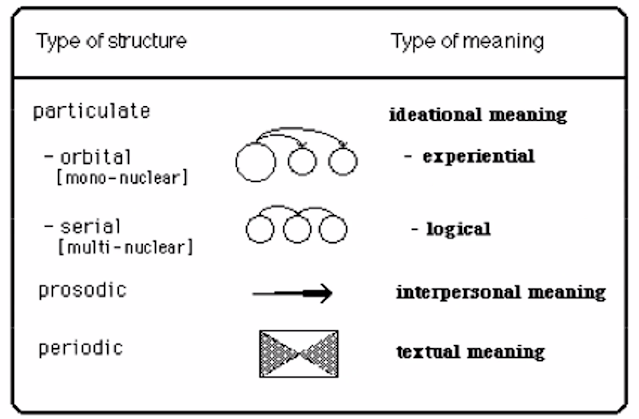

Like much of its framework, SFL offers a very elaborate model of structure. Its metafunctional distribution of periodic, prosodic and particulate structures is well known, with numerous distinctions within each type (Halliday 1979). Focusing on particulate structures, Halliday distinguishes between multivariate and univariate structures, and within univariate structures, between hypotactic and paratactic structures (Halliday 1965, Halliday and Matthiessen 2014), while Martin (1996) conceptualises particulate structures as involving orbital and serial relations (Martin 1996). Similarly, relations in discourse are alternatively conceptualised from the perspective of grammar as non-structural (Halliday and Hasan 1976) or from discourse semantics as involving co-variate structures (Martin 1992, adapted from Lemke 1985).

Many of these types of structure are sharply distinct, while others have significant overlap. Together, they account for a wide range of linguistic phenomena and do a good job at describing the patternings that occur across regions of language. However as SFL has expanded its descriptive framework into a wider range of languages, it has been clear that there are grammatical constructions that are not quite accounted for. Building upon this work, this talk offers a generalised model of particulate structure, developed with Jim Martin, that aims to cover a wider range of grammatical patterns.

This model does not start with types of structure, but rather with three sets of factors that can be combined relatively freely: whether the structures involves a nucleus and subordinate satellites (nuclearity), whether there is linear interdependency between the elements in the structure (linearity), and whether the relations can occur more than once (iteration). These factors generate a wider set of structures than so far acknowledged explicitly in SFL. Together, they offer a means of seeing both the differences between types of structure already acknowledged, as well as variation within them. They also generate structures that account for phenomena not yet considered structurally in SFL to date.

The goal of this talk is build more explicitness in SFL’s model of structure as it continues its descriptive expansion and in doing so, help clarify issues that have often been left aside in SFL grammatical description. Where possible, the model will be exemplified through English but I will bring in other languages as need be.

Blogger Comments:

[1] To be clear, Halliday soon after revised his model of grammatical structure types in favour of the current typology. Halliday (1994: 36) :

[2] To be clear, as demonstrated here and here, Martin's orbital vs serial distinction purports to model the structural distinction for the experiential vs logical metafunctions, but actually models the distinction between hypotaxis (nucleus vs satellite status) and parataxis (nuclei of the same status).

[3] To be clear, these are cohesive relations at the level of lexicogrammar, and Halliday & Matthiessen (2014) provides an updated interpretation.

[4] To be clear, by 1992, Lemke had already recanted his view that 'covariate' was a type of structure. Lemke (1988: 159):

My own 'covariate structure' (Lemke 1985), which includes Halliday's univariate type, is for the case of homogeneous relations of co-classed units, and should perhaps be called a 'structuring principle' rather than a kind of structure.

[5] To be clear, this remains a bare assertion until it is supported by evidence. The previous attempt to provide such evidence, Martin's seminar of 13/8/21, was demonstrated to be based on theoretical misunderstandings (see here).

[6] To be clear, Doran's work builds on Martin's misunderstanding of structure; see [2].

[7] To be clear, here Doran is modelling metalanguage (SFL Theory), not language, by essentially devising a metalinguistic system of features ("factors") that generates types of structure, as if metalanguage were language.

[8] To be clear, each of these factors is theoretically problematic.

Firstly, nuclearity corresponds to Martin's orbital structure, which purports to be a model of experiential structure, but is actually a model of logical hypotaxis (independent nucleus vs dependent satellites). That is, nuclearity misconstrues a multivariate structure as a univariate structure.

Secondly, linear interdependency is just interdependency. The word 'linear' is redundant, since all structures are linear. (For Halliday (1965), univariate structures are lineally recursive.) Linear interdependency corresponds to Martin's serial structure, which purports to be a model of the univariate structure of the logical metafunction, but is actually just a model of one of its dimensions: parataxis (multiple nuclei of the same status).

Thirdly, in SFL Theory, iteration describes the type of structure favoured by the logical metafunction (Halliday (1994: 36). The purpose of introducing Halliday's term here is to provide the possibility of 'iterative nuclearity' and 'non-iterative linear interdependency'; see [9].

To summarise, Doran's three factors actually concern:

- hypotactic interdependency

- paratactic interdependency

- interdependency in general.