Matters Arising Within Systemic Functional Linguistic Theory And Its Community Of Users

Monday, 27 December 2021

Rhyme Without Reason

Tuesday, 21 December 2021

Bondicons, Heroes And Ideology

Bertrand Russell History Of Western Philosophy (pp 21-2):

Throughout this long development, from 600 BC to the present day, philosophers have been divided into those who wished to tighten social bonds and those who wished to relax them. With this difference, others have been associated.

The disciplinarians have advocated some system of dogma, either old or new, and have therefore been compelled to be, in greater or lesser degree, hostile to science, since their dogmas could not be proved empirically. They have almost invariably taught that happiness is not the good, but that ‘nobility’ or ‘heroism’ is to be preferred. They have had a sympathy with irrational parts of human nature, since they have felt reason to be inimical to social cohesion.

The libertarians, on the other hand, with the exception of the extreme anarchists, have tended to be scientific, utilitarian, rationalistic, hostile to violent passion, and enemies of all the more profound forms of religion.

This conflict existed in Greece before the rise of what we recognise as philosophy, and is already quite explicit in the earliest Greek thought. In changing forms, it has persisted down to the present day, and no doubt will persist for many ages to come.

Monday, 20 December 2021

Promotion Material

Monday, 13 December 2021

Evidence-Based vs "Evidence-Based"

Wednesday, 8 December 2021

The 'Transcendent' vs 'Immanent' Views of Meaning Explained

The 'transcendent' view of meaning holds that there is meaning outside of language and other semiotic systems.

The 'immanent' view of meaning holds that all meaning is within language and other semiotic systems.

To illustrate, imagine the scenario of a person seeing a cat in a backyard.

From the 'transcendent' perspective, 'a cat in a backyard' is meaning that is outside of language. Only if the person says 'there is a cat in the backyard' is the meaning inside language, in which case, it is said to refer to meanings outside semiotic systems. Reality is outside language, and language refers to it.

From the 'immanent' perspective, 'a cat in a backyard' is meaning that is inside language: a mental projection of meaning (rather than a verbal projection of wording). This entails a token-value relation between meanings of perceptual systems and the meanings of linguistic systems: perceptual tokens realise linguistic values. The meanings of perceptual systems are construed as the meanings of linguistic systems. Reality is what language construes of what perceptual systems construe.

Monday, 6 December 2021

Playing The System

Monday, 29 November 2021

Successful Meeting

Monday, 22 November 2021

Saturday, 20 November 2021

The Function Of Thematic Equatives

A thematic equative (which is usually called a ‘pseudo-cleft sentence’ in formal grammar) is an identifying clause which has a thematic nominalisation in it. Its function is to express the Theme-Rheme structure in such a way as to allow for the Theme to consist of any subset of the elements of the clause. This is the explanation for the evolution of clauses of this type: they have evolved, in English, as a thematic resource, enabling the message to be structured in whatever way the speaker or writer wants.Let us say more explicitly what this structure means. The thematic equative actually realises two distinct semantic features, which happen to correspond to the two senses of the word identify. On the one hand, it identifies (specifies) what the Theme is; on the other hand, it identifies it (equates it) with the Rheme.The second of these features adds a semantic component of exclusiveness: the meaning is ‘this and this alone’. So, the meaning of what the duke gave my aunt was that teapot is something like ‘I am going to tell you about the duke’s gift to my aunt: it was that teapot — and nothing else’. Contrast this with the duke gave my aunt that teapot, where the meaning is ‘I am going to tell you something about the duke: he gave my aunt that teapot’ (with no implication that he did not give – or do – other things as well).Hence even when the Theme is not being extended beyond one element, this identifying structure still contributes something to the meaning of the message: it serves to express this feature of exclusiveness. If I say what the duke did was give my aunt that teapot, the nominalisation what the duke did carries the meaning ‘and that’s all he did, in the context of what we are talking about’.This is also the explanation of the marked form, which has the nominalisation in the Rheme, as in that’s the one I like. Here the Theme is simply that, exactly the same as in the non-nominalised equivalent that I like; but the thematic equative still adds something to the meaning, by signalling that the relationship is an exclusive one – I don’t like any of the others. Compare a loaf of bread we need and a loaf of bread is what we need. Both of these have a loaf of bread as Theme; but whereas the former implies ‘among other things’, the latter implies ‘and nothing else’.Note that some very common expressions have this marked thematic equative structure, including all those beginning that’s what, that’s why, etc.; e.g. that’s what I meant, that’s why it’s not allowed.

Monday, 15 November 2021

Updating Opinions

Monday, 8 November 2021

A Trap For Young Postgrads

Saturday, 6 November 2021

Virtuous Circles

Thursday, 4 November 2021

The SFL Approach To Grammar

To understand [grammatical] categories, it is no use asking what they mean. The question is not ‘what is the meaning of this or that function or feature in the grammar?’; but rather ‘what is encoded in this language, or in this register (functional variety) of the language?’ This reverses the perspective derived from the history of linguistics, in which a language is a system of forms, with meanings attached to make sense of them. Instead, a language is treated as a system of meanings, with forms attached to express them. Not grammatical paradigms with their interpretation, but semantic paradigms with their realisations.

So if we are interested in the grammatical function of Subject, rather than asking ‘what does this category mean?’, we need to ask ‘what are the choices in meaning in whose realisation the Subject plays some part?’ We look for a semantic paradigm which is realised, inter alia, by systematic variation involving the Subject: in this case, that of speech function, in the interpersonal area of meaning. This recalls Firth’s notion of ‘meaning as function in a context’; the relevant context is that of the higher stratum – in other words, the context for understanding the Subject is not the clause, which is its grammatical environment, but the text, which is its semantic environment.

Monday, 1 November 2021

Monday, 25 October 2021

Education vs Examination Performance

Monday, 18 October 2021

Monday, 11 October 2021

The Needy Student

Saturday, 9 October 2021

How To Test Whether a Clause Is Behavioural

Monday, 4 October 2021

Perceived Credibility

Tuesday, 28 September 2021

'Fail To Do' vs 'Forget To Do'

'fail to do' is (trying but) not succeeding (Halliday & Matthiessen 2014: 572)

whereas

'forget to do' is not doing according to intention (Halliday & Matthiessen 2014: 574).

Monday, 27 September 2021

University Management

Monday, 20 September 2021

Thursday, 16 September 2021

The Postmodifier

But the Postmodifier does not itself enter into the logical structure, because it is not construed as a word complex.

Monday, 13 September 2021

Monday, 6 September 2021

Tuesday, 31 August 2021

Theoretical Problems With Doran's 'Factoring Out Structure: Nuclearity, Linearity And Iteration'

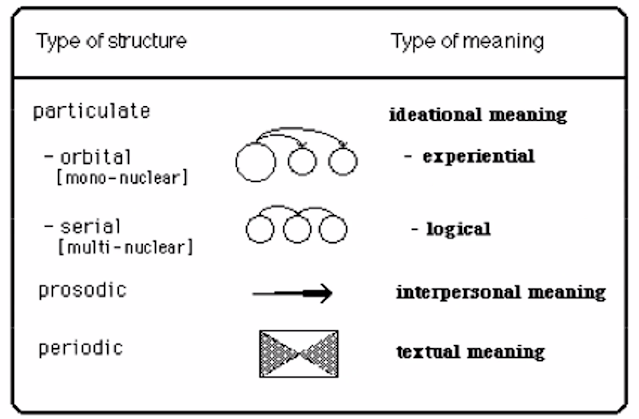

Like much of its framework, SFL offers a very elaborate model of structure. Its metafunctional distribution of periodic, prosodic and particulate structures is well known, with numerous distinctions within each type (Halliday 1979). Focusing on particulate structures, Halliday distinguishes between multivariate and univariate structures, and within univariate structures, between hypotactic and paratactic structures (Halliday 1965, Halliday and Matthiessen 2014), while Martin (1996) conceptualises particulate structures as involving orbital and serial relations (Martin 1996). Similarly, relations in discourse are alternatively conceptualised from the perspective of grammar as non-structural (Halliday and Hasan 1976) or from discourse semantics as involving co-variate structures (Martin 1992, adapted from Lemke 1985).

Many of these types of structure are sharply distinct, while others have significant overlap. Together, they account for a wide range of linguistic phenomena and do a good job at describing the patternings that occur across regions of language. However as SFL has expanded its descriptive framework into a wider range of languages, it has been clear that there are grammatical constructions that are not quite accounted for. Building upon this work, this talk offers a generalised model of particulate structure, developed with Jim Martin, that aims to cover a wider range of grammatical patterns.

This model does not start with types of structure, but rather with three sets of factors that can be combined relatively freely: whether the structures involves a nucleus and subordinate satellites (nuclearity), whether there is linear interdependency between the elements in the structure (linearity), and whether the relations can occur more than once (iteration). These factors generate a wider set of structures than so far acknowledged explicitly in SFL. Together, they offer a means of seeing both the differences between types of structure already acknowledged, as well as variation within them. They also generate structures that account for phenomena not yet considered structurally in SFL to date.

The goal of this talk is build more explicitness in SFL’s model of structure as it continues its descriptive expansion and in doing so, help clarify issues that have often been left aside in SFL grammatical description. Where possible, the model will be exemplified through English but I will bring in other languages as need be.

Blogger Comments:

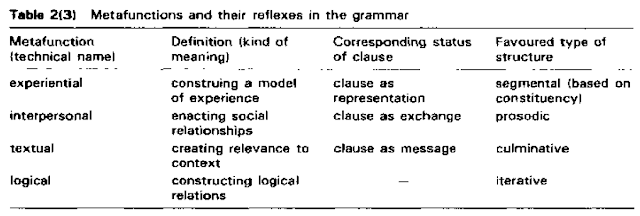

[1] To be clear, Halliday soon after revised his model of grammatical structure types in favour of the current typology. Halliday (1994: 36) :

[2] To be clear, as demonstrated here and here, Martin's orbital vs serial distinction purports to model the structural distinction for the experiential vs logical metafunctions, but actually models the distinction between hypotaxis (nucleus vs satellite status) and parataxis (nuclei of the same status).

[3] To be clear, these are cohesive relations at the level of lexicogrammar, and Halliday & Matthiessen (2014) provides an updated interpretation.

[4] To be clear, by 1992, Lemke had already recanted his view that 'covariate' was a type of structure. Lemke (1988: 159):

My own 'covariate structure' (Lemke 1985), which includes Halliday's univariate type, is for the case of homogeneous relations of co-classed units, and should perhaps be called a 'structuring principle' rather than a kind of structure.

[5] To be clear, this remains a bare assertion until it is supported by evidence. The previous attempt to provide such evidence, Martin's seminar of 13/8/21, was demonstrated to be based on theoretical misunderstandings (see here).

[6] To be clear, Doran's work builds on Martin's misunderstanding of structure; see [2].

[7] To be clear, here Doran is modelling metalanguage (SFL Theory), not language, by essentially devising a metalinguistic system of features ("factors") that generates types of structure, as if metalanguage were language.

[8] To be clear, each of these factors is theoretically problematic.

Firstly, nuclearity corresponds to Martin's orbital structure, which purports to be a model of experiential structure, but is actually a model of logical hypotaxis (independent nucleus vs dependent satellites). That is, nuclearity misconstrues a multivariate structure as a univariate structure.

Secondly, linear interdependency is just interdependency. The word 'linear' is redundant, since all structures are linear. (For Halliday (1965), univariate structures are lineally recursive.) Linear interdependency corresponds to Martin's serial structure, which purports to be a model of the univariate structure of the logical metafunction, but is actually just a model of one of its dimensions: parataxis (multiple nuclei of the same status).

Thirdly, in SFL Theory, iteration describes the type of structure favoured by the logical metafunction (Halliday (1994: 36). The purpose of introducing Halliday's term here is to provide the possibility of 'iterative nuclearity' and 'non-iterative linear interdependency'; see [9].

To summarise, Doran's three factors actually concern:

- hypotactic interdependency

- paratactic interdependency

- interdependency in general.

Monday, 30 August 2021

Saturday, 28 August 2021

Classifier + Thing (Or Compound Noun?)

A sequence of Classifier + Thing may be so closely bonded that it is very like a single compound noun, especially where the Thing is a noun of a fairly general class, e.g. train set (cf. chemistry set, building set). In such sequences the Classifier often carries the tonic prominence, which makes it sound like the first element in a compound noun. Noun compounding is outside the scope of the present book; but the line between a compound noun and a nominal group consisting of Classifier + Thing is very fuzzy and shifting, which is why people are often uncertain how to write such sequences, whether as one word, as two words, or joined by a hyphen (e.g. walkingstick, walking stick, walking-stick).

The relation between Classifier and Thing may be elaborating, extending or enhancing. Halliday & Matthiessen (1999: 183):

Friday, 27 August 2021

Reading An Image

- the point of departure, christianity, as new and ideal

- the endpoint, atheism, as given and real.

Monday, 23 August 2021

Saturday, 21 August 2021

One Of The Problems With Martin's Model Of Structure Types

Monday, 16 August 2021

A Human Sacrifice To Appease The Woke Nazis

Sunday, 15 August 2021

Some Problems With Martin's Notion Of A 'Subjacency Duplex Structure'

Halliday, M A K 1981 (1965) Types of Structure. M A K Halliday & J R Martin [Eds.] Readings in Systemic Linguistics. London: Batsford. 29-41.Halliday, M A K 1979 Modes of meaning and modes of expression: types of grammatical structure, and their determination by different semantic functions. D J Allerton, E Carney, D Holcroft [Eds] Function and Context in Linguistics Analysis: essays offers to William Haas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 57-79Rose, D 2001 The Western Desert code: an Australian cryptogrammar. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

The nominal group, as we have seen, construes an entity — something that could function directly as a participant.

Monday, 9 August 2021

Halliday (1979) On Logical Structure As Recursive

In the logical mode, reality is represented in more abstract terms, in the form of abstract relations which are independent of and make no reference to things. …

Since we are claiming these structural manifestations are only tendencies, such an argument is only tenable on the grounds that the type of structure that is generated by the logical component is in fact significantly different from all the other three. The principle is easy to state: logical structures are recursive. …

True recursion arises when there is a recursive option in the network, of the form shown in Figure 14, where A:x,y,z… n is any system and B is the option ‘stop or go round again’. This I have called “linear recursion”; it generates lineally recursive structures of the form a₁ + a₂ + a₃ + . . . (not necessarily sequential):

… Logical structures are different in kind from all the other three. In the terms of systemic theory, where the other types of structure – particulate (elemental), prosodic and periodic – generate simplexes (clauses, groups, words, information units), logical structures generate complexes (clause complexes, group complexes, etc.) (Huddleston 1965). … While the point of origin of a non-recursive structure is a particular rank – each one is a structure “of” the clause, or of the group, etc. – recursive structures are in principle rank-free: coordination, apposition, subcategorisation are possible at all ranks.

Postscript:

In his seminar paper (13/8/21) on 'construing entities', Martin claimed that there are no recursive networks anywhere in the SFL literature. The network above occurs in one of the references he provided.

Saturday, 7 August 2021

Why Martin's Notion Of 'Commitment' Is Theoretically Invalid

Instantiation also opens up theoretical and descriptive space for considering commitment (Martin 2008, 2010), which refers to the amount of meaning instantiated as the text unfolds. This depends on the number of optional systems taken up and the degree of delicacy pursued in those that are, so that the more systems entered, and the more options chosen, the greater the semantic weight of a text (Hood 2008).